What If They Say Yes?

Revised Suicide Prevention Protocols Give Nurses a Tool for Connection and Care

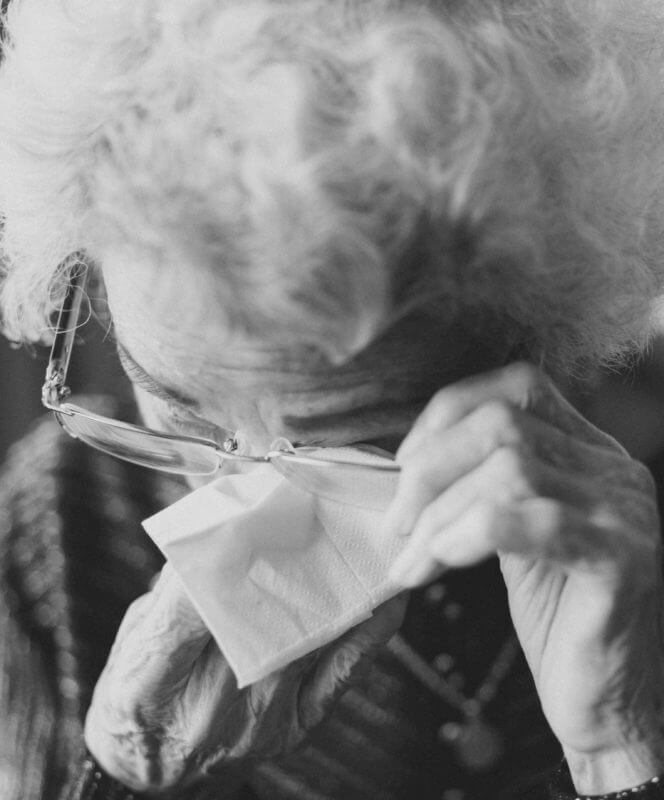

Ruth, a woman in her 70s, recently found herself in a CentraCare hospital for a chronic medical condition.

There was nothing on her chart about past mental health issues, but on discharge day, her nurse, Kim, noticed that something felt off: Ruth was distant and seemed depressed. Kim sat down with her and asked how she’s doing. “I’m afraid to go home,” Ruth revealed.

Questions shot through Kim’s mind: why, medically, is she afraid? Does she need an occupational or physical therapist, or some other resource, to help with the transition home? Or was there something else?

Eventually Ruth (not her real name) shared that her husband had recently passed and she’d be returning to an empty house. She feared she’d no longer be able to live on her own.

(Editor’s note: the patient’s name and details in this story have been changed.)

I’m afraid to go home.”

Ruth , centracare Patient

The response triggered other questions in Kim’s mind—the six from the Columbia Suicide Severity Risk Scale (C-SSRS) protocol. Ruth, like all CentraCare hospital patients over age 10, was screened upon admission. At that time she was considered “no risk,” but concerned that Ruth’s mental state had changed since then, Kim used the questions to dig deeper. She discovered that Ruth was experiencing more than worry about returning home: she was having thoughts about ending her life.

The case underscores the power of the Columbia screener

The case underscores the power of the Columbia screener, says Lisa Bershok, CentraCare’s Suicide Prevention Program Manager. For Kim, the evidence-based tool provided a gut-check: the questions gave her a structured way to open a human conversation with Ruth and confirm what her nurse’s intuition had already suggested.

“Had Kim not utilized the Columbia, then it might have just been a discussion around the fact that she’s grieving, she’s sad, she’s afraid to go home,” says Bershok. “But because she did, she determined the woman did have thoughts of dying by suicide, and we were able to get her assessed and connected with resources.”

Today, the Columbia screener is a regular part of life at CentraCare hospitals and emergency departments. It’s used every day with all patients over age 10. The tool complements the more general psychosocial well-being assessments long utilized at CentraCare to gauge a patient’s mental state, but with one distinction: it’s specific, getting directly at the risk of death by suicide.

And in medical settings, when people are in pain or facing an uncertain future, these risks are much higher. Research shows that nine physical health conditions are risk factors for suicide, from congestive heart failure to back pain, cancer to sleep disorders. Add to that the typical warning signs of suicide—hopelessness and lack of connection—which can be exacerbated in cases of unexpected medical diagnoses, intense pain, or long hospitalizations, and the use of the protocol is even more critical.

Fortunately, the Columbia screener is a highly effective tool. One large health system that operates 40 hospitals in four states reported a 50 percent reduction in suicide since implementing C-SSRS in 2019.

The research shows that asking somebody about their thoughts related to suicide is more predictive of preventing suicide death than tracking cholesterol scores is to preventing heart attacks.”

Lisa Bershok, CentraCare’s Suicide Prevention Program Manager

“The research shows that asking somebody about their thoughts related to suicide is more predictive of preventing suicide death than tracking cholesterol scores is to preventing heart attacks,” Bershok says.

That link—between what happens in your head and in the rest of your body—is key to another goal of C-SSRS use: destigmatizing mental health.

“We want it to be seen similarly to how a med/surg nurse might be listening to lung sounds—to normalize it as just another part of their job,” says Jennifer Burris, Director of Nursing Practice at St. Cloud Hospital. “It decreases a stigma behind talking about mental health in general, and it helps us do our job completely so that we’re taking care of the entire patient.”

If someone answers “Yes” to a Columbia question—that they have thought about ending their lives—there’s a set of protocols to be enacted in response by an interdisciplinary team.

While the culture of caring for the whole person permeates CentraCare, there is some fear among nursing staff around suicide risk, says Jodi Lillemoen, core charge nurse at St. Cloud Hospital. “It’s always in the back of your mind: If they do say yes, what do I do and how do I respond? But the tools are there.”

Fear is a normal thing with any of the assessments we do. Even for those of us who work in mental health, we’re always nervous if somebody answers yes. Are we going to do the right thing at the right time?”

Julie Abfalter, columbia protocol trainer at centracare

Such anxieties are part of the job whether you’re in a medical or behavioral health unit, says Julie Abfalter, who trains CentraCare’s mental health nurses on the protocol. “Fear is a normal thing with any of the assessments we do. Even for those of us who work in mental health, we’re always nervous if somebody answers yes. Are we going to do the right thing at the right time? But it’s the same as if we have a patient who comes in and is having chest pain: are we doing the right thing at the right time? That fear and that adrenaline is a normal human response. Having the right tool in those moments makes all the difference.”

For additional support resources and staff tools, visit the Suicide Prevention Resources page on CentraNet.

Universal Suicide Screening at All CentraCare Hospitals

As of Oct. 25, all eight CentraCare hospitals are screening daily for suicide using the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (CSSRS).